Code Green Solutions

Not all community developers are aware that the work they’re doing has the potential to improve health, but the East Bay Asian Local Development Corporation (EBALDC) has built health into its strategic plan, and in the neighborhood revitalization work of the San Pablo Area Revitalization Collaborative (SPARC), convened by EBALDC, health is the first priority. The San Pablo Avenue Corridor neighborhood that stretches between downtown Oakland and nearby Emeryville is one of the poorest and most disadvantaged areas of Oakland, California. Here, life expectancy is up to 20 years lower than just a few miles away in the Oakland Hills.

Not all community developers are aware that the work they’re doing has the potential to improve health, but the East Bay Asian Local Development Corporation (EBALDC) has built health into its strategic plan, and in the neighborhood revitalization work of the San Pablo Area Revitalization Collaborative (SPARC), convened by EBALDC, health is the first priority.

The San Pablo Avenue Corridor neighborhood that stretches between downtown Oakland

and nearby Emeryville is one of the poorest and most disadvantaged areas of Oakland, California. Here, life expectancy is up to 20 years lower than just a few miles away in the Oakland Hills.

SPARC works in the San Pablo Avenue Corridor addressing the physical, social and economic factors—“social determinants”—that shape residents’ health. SPARC partners work together to create healthier places for residents throughout the neighborhood. EBALDC executive director Josh Simon says the question they ask themselves is, “How do we put healthy activities here, so that people come to San Pablo Avenue for healthy opportunities instead of illegal ones?”

Several decades of community development experience have led EBALDC to build deep partnerships with government agencies such as the City of Oakland, the Alameda County Public Health Department, and the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, with community residents, and with other neighborhood organizations. These partnerships, together with past experience in which effective cross-sector collaboration didn’t quite materialize, led EBALDC to propose a more structured “collective impact” approach to guide SPARC’s work.

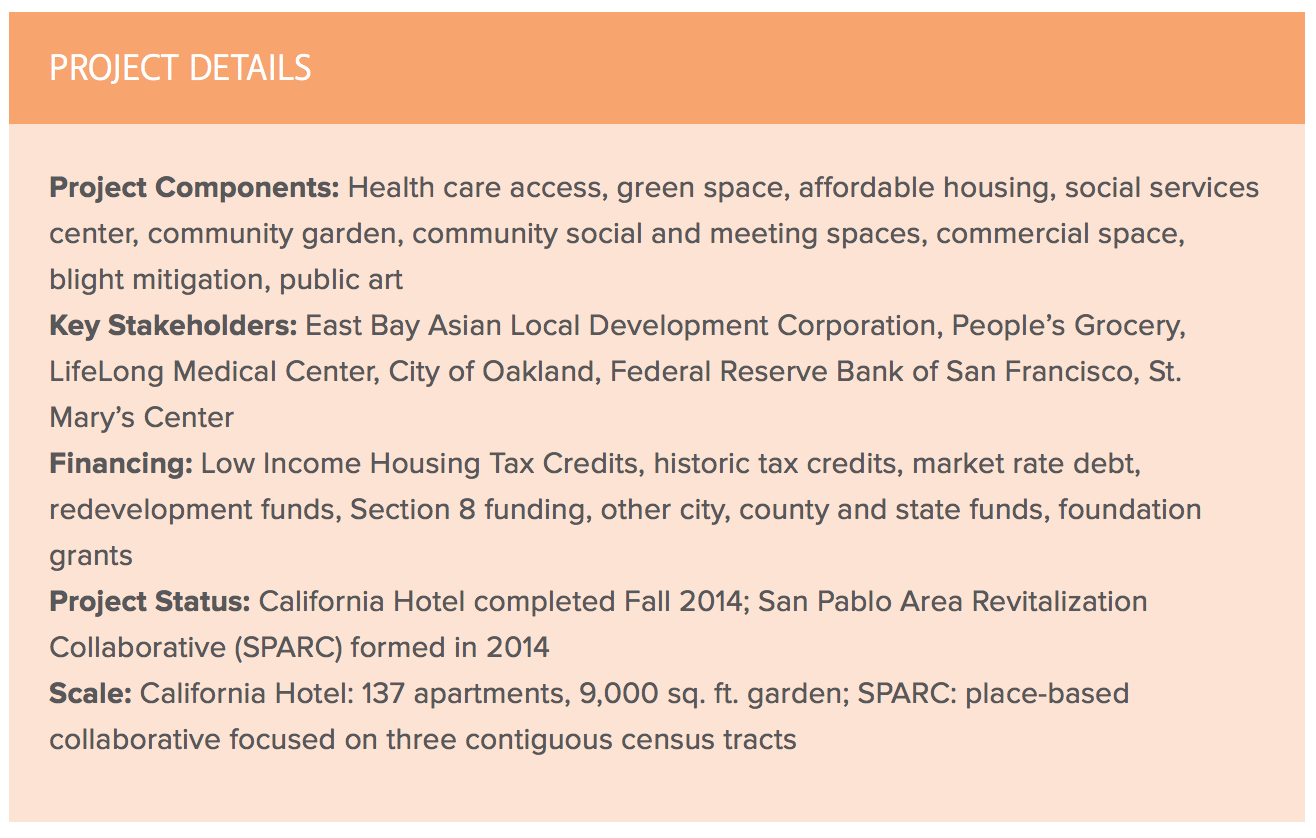

Renovation of the California Hotel, located on San Pablo Avenue, is a part of this effort. As one of the few hotels hospitable to African Americans in the mid-1900s, the California Hotel hosted many of the popular jazz musicians and other musical luminaries of the era, and many also performed there during their stays. The hotel is now listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

However, in the 1950s the state built a new freeway nearby, slashing through and dividing this West Oakland neighborhood. By the 1980s the hotel was converted to single room occupancy (SRO) housing by another nonprofit affordable housing developer. Over time, the hotel fell into disrepair from neglect, lack of continued investment, and increasing neighborhood violence and social disintegration.

Eventually, that developer and manager of the hotel went out of business. The city tried to evict the tenants to tear down the building, but a handful of disabled and elderly low-income residents of the hotel, supported by the grassroots social justice group Causa Justa::Just Cause, organized, and in 2008 convinced the city that the building should be renovated instead. By this time, EBALDC was well established and had already committed to deepening its work along San Pablo Avenue. When the hotel went on the market in 2011, EBALDC bought the property and made the hotel its flagship project along the corridor.

The hotel’s SRO rooms were converted into individual apartments, and the work was done sequentially so that existing residents could remain in place during renovation. EBALDC also engaged with partners to address other factors that impact residents’ health. People’s Grocery, a healthy food access organization in Oakland, joined the effort and converted one third of the former parking lot into a thriving 9,000 square foot community garden, with an outdoor kitchen and lively gathering space.

LifeLong Medical Care, a nearby Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC), placed three social workers on staff at the hotel to serve the needs of residents. Dedicated funding from the city of Oakland was also obtained to support an onsite resident services coordinator, and a community organizer to build social connection and resilience and cultivate resident leadership.

Renovations, including adding solar panels, made the building energy efficient, and the project has been “GreenPoint Rated” by California’s Build it Green, a certification program akin to the LEED program for residential home construction in California.

While a single brick-and-mortar project is important, EBALDC believes it will only have significant impact on community members’ lives if it is integrated with and supported by a healthy neighborhood ecosystem. In 2008, EBALDC acquired a number of additional properties in the neighborhood in order to develop affordable workforce housing for residents earning up to 80 percent of the area median income. “We want to have a community that is mixed income, to reduce displacement of long-time residents,” says Simon. “Residential stability requires housing that is affordable for a wide range of incomes.” In addition, anchoring either end of the San Pablo Avenue Corridor are two earlier EBALDC housing complexes, Avalon Senior Housing in Emeryville, and the San Pablo Hotel, also serving seniors, in downtown Oakland.

Yet in order to truly tackle neighborhood level revitalization, cross-sector collaboration is essential. EBALDC had the California Hotel as an anchor project in the San Pablo Avenue Corridor. EBALDC had multiple partners from this and other projects in the area and did outreach to other organizations working along San Pablo Avenue and to residents of the neighborhood. EBALDC then brought all of this together to initiate what in 2014 became the San Pablo Avenue Revitalization Collaborative or SPARC.

SPARC is pursuing an approach that focuses not only on systems and places but also on implementing strong people-based strategies. It initially sponsored a neighborhood artist to create two trash can murals in the San Pablo Avenue Corridor, and that same artist has secured additional funding for two more. Residents can apply for mini-grants from the California Hotel’s community organizing project to initiate community improvements. There is a walking club for seniors, and seniors are also advocating with the city for the installation of bus shelters.

SPARC hosted a neighborhood walk to identify hot spots for blight and illegal dumping and is convening a community design charrette and “build days” to transform those spots into neighborhood sources of pride. People’s Grocery holds a weekly “Flavas of the Garden” at the California Hotel for neighborhood residents, and kids hang out in the garden after school. All of these activities work to build social capital, a sense of community, and more “eyes on the street,” with neighborhood improvements driven by the people living there.

Partnerships

A number of organizations and agencies that had been working in the San Pablo Avenue neighborhood for years came together with EBALDC to take on the larger project of revitalizing the corridor. In 2014, they formalized the collaborative as SPARC, and the partners developed a five-year action plan to improve neighborhood health and well-being (for an overview, see the SPARC Action Plan one-pager). Each partner organization participates in the work within the neighborhood in ways that fulfill its own mission, and each secures its own resources to implement its work here. Says EBALDC Healthy Neighborhoods Manager Romi Hall, “We all hold the pieces to improve neighborhood health.”

Core partners include:

These organizations and residents became the steering committee for SPARC. Part of the impetus to adopt the collective impact approach comes from EBALDC’s past experience. In 1984, it built the Asian Resource Center in downtown Oakland to house organizations serving Oakland’s Chinatown community in a single building. The goal was more collaboration across these organizations.

Though subsequent community hub projects were built, none achieved the expected transformative collaborations. In contrast, “collective impact” is more deliberate, and involves convening organizations and residents to engage in data-driven strategic thinking about neighborhood improvement, and in aligned individual, organizational and collective activity to achieve change.

The five pillars of the collective impact approach are:

A 2014 grant from the Partners in Progress initiative supported EBALDC’s role as a “community quarterback,” and indeed made possible the planning process that resulted in SPARC. The grant enables steering committee members to work in an intentional and coordinated manner, with EBALDC serving as the collective impact “backbone support organization.” The funding pays for an EBALDC staff member to coordinate coalition meetings and activities, and provides stipends to partner organizations and community residents to participate. This allows for the “continuous communication” the group needs to work collectively.

The coalition identified several aspects of neighborhood life to work on, but knew they needed to prioritize. In a series of strategic planning sessions and community input sessions, the partners identified health, housing, community cohesion, economy and partnerships as the focus areas for their work. They decided to start with health.

Guided by this “common agenda,” individual organizations’ decisions about which projects to pursue now aim strategically to serve the larger vision, in an increasingly aligned array of “mutually reinforcing activities.” This is shaping EBALDC’s own development decisions, as well. With a common vision, collaborative members are able to make strategic decisions, in the moment, in response to emerging opportunities, while staying firmly rooted in the common goals.

Financing

The California Hotel was renovated using nine percent Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) investment, historic preservation tax credits, market rate investment, and an array of city, county and state funding. Because the California Hotel is a permanent supportive housing project, operating costs including resident social services are projected to be $333,000 annually. According to Simon, California Hotel operating revenue will partially cover the costs, and will be supplemented with sustained funding for services from Medicaid and several branches of Alameda County Behavioral Health Care Services. [See financing details here].

The initial plan for the California Hotel had been to designate between 25 and 35 percent of the units for “special needs” residents. “We adjusted along the way,” explains Simon, “as we realized the population had higher service needs.” In the end, 80 percent of hotel residents receive social services. Project-based vouchers (Section 8) subsidize rents. In addition, the hotel has 10 designated units for residents who qualify under the Mental Health Services Act, 15 wheelchair accessible units, and 7 units for residents with hearing or visual disabilities.

Funding for the initial SPARC convening, planning and coordination is provided through the Partners in Progress grant to EBALDC. In 2014 the Partners in Progress initiative, launched by Citibank Foundation and the Low Income Investment Fund (LIIF), funded 14 grantees to serve as community quarterbacks. The $250,000 grant enabled EBALDC to bring Hall on board to support the neighborhood-wide SPARC work, and covers some of the cost of convening SPARC partners and coordinating SPARC planning processes.

In 2015, the group received a BUILD Health Challenge grant, which provides $250,000 over two years to support the overall implementation of SPARC. The grant, designed to fund such collaboration, supports partnership among EBALDC (a community-based organization), the community benefits department of Alta Bates Summit Medical Center- Sutter Health, and the Alameda County Public Health Department. Sutter Health provided the required match, providing $308,000 in in-kind and cash support.

EBALDC, on SPARC’s behalf, will continue to pursue additional funding to support the quarterback role and the cross-sector collaboration activities.

Turning Points

Measurement and Outcomes

“Shared measurement systems” are a pillar of the collective impact approach, and data have played an important role in the strategic planning process for SPARC, including health department data, demographic information and social data, city planning office reports, and data on neighborhood parcels.

The American Community Survey revealed that the neighborhood is approximately 80 percent renters. Crime data have helped identify hotspots for drugs, violence, and prostitution, and helped locate these hotspots in relationship to liquor stores up and down the corridor. The SPARC coalition is also talking with Alta Bates Summit Medical Center about using hospital data.

“We use a lot of infographics to help share and paint the data as a story, ” says Hall. Infographics and maps have been particularly helpful during meetings and conversations. “We have an EBALDC staffer who is a ‘data whisperer’,” Hall confides, helping the coalition to identify data sources and make sense of the information.

The coalition also conducted a brief community resident survey as part of a photo booth activity at a community event. Data gathered about community concerns fully aligned with information from other sources, for example identifying hypertension as a top health issue.

Although SPARC used a wide array of data to inform its strategic planning, the question of which metrics should be used to assess progress and outcomes is more challenging. SPARC chose to focus on health and well-being as its starting point. And yet the coalition believes there are many interlocking factors critical to improving health, beyond the biomedical. SPARC is looking for ways to measure outcomes that will assess improvements in overall wellbeing, i.e. non-medical factors, yet that are concrete and specific enough to help define its activities, track its progress, and allow it to course-correct as needed.

In 2014 SPARC hired evaluator Social Policy Research Associates (SPR) and formed an advisory committee that includes an academic researcher who specializes in community health metrics, representatives from the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, Alameda County Public Health Department, Alta Bates Summit Medical Center, Kaiser Permanente, and others. An ongoing challenge the group foresees is finding sufficiently granular sources of data at the neighborhood level.

SPR has worked with SPARC partners to articulate the collaborative’s theory of change. The SPARC steering committee and its metrics advisory committee are using an “adaptive management” approach, an iterative process by which the group acts based on current knowledge, assesses the results, and uses that information to guide the next action. Adaptive management balances long-term, strategic thinking with short-term action that can be adjusted, as a way to stay nimble in an emerging and complex situation. SPR is developing an evaluation approach that provides iterative information to guide decision-making as the neighborhood, its needs and opportunities, and SPARC itself, evolve.

Lessons From the Project Team