Code Green Solutions

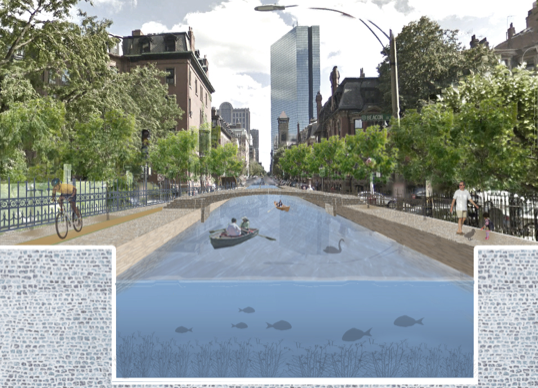

Back Bay Canals proposed by Dennis Carlberg, Arlen Stawaz, and Michael Wang at the Urban Land Institute, Boston

While many campuses are pursuing clean energy visions with vigor and determination, others recognize that preparing for climate impacts has become essential. Boston University (BU), in concert with a myriad of local city partners, recently recognized that given climate change threats, the City of Boston now ranks 8th in the world for flooding and storm risks. Considering these findings, together they decided to take action to discover what can be done. BU research teams have identified new vulnerable locations on Boston’s shoreline from which the University could be flooded, and convened the conversation to explore solutions- both on-campus and city-wide.

As Snehal Desai has recognized, the water/energy nexus is demanding urgent clean technology innovation: BU recognizes that this same water/energy nexus places their entire city at risk and seeks to design system-wide solutions.

So does your clean energy vision recognize such opportunities for climate resilience?

Do you know which climate impact risks are highest in your region?

What kinds of actions can be taken to address climate adaptation risk?

Join BU as it gets climate-ready… And join BU faculty and students, via @sustainableBU, during our #cleanenergyu conversation this Earth Week to ask questions about their clean energy 2025 vision – while sharing yours!

by Dennis Carlberg:

In 2013, the City of Boston announced Climate Ready Boston, outlining its efforts to understand the challenges of preparing for the impacts of climate change in the city. Boston University is following the City’s lead by exploring the challenges the University will need to address in the face of rising seas, higher temperatures and more intense storms.

To study these climate challenges, the University, led by sustainability@BU, assembled a team comprised of graduate students Eric Bullock, Molly Wilder, Tyler Lockamy from Professor Suchi Gopal’s graduate Remote Sensing and GIS class; BU faculty climate scientists; and operations departments from Facilities, Management & Planning to Emergency Response Planning. BU also worked with outside organizations that are assessing their own vulnerabilities, including the City of Boston, Boston Water & Sewer Commission, the Massachusetts Department of Transportation, the City of Cambridge, the Metropolitan Area Planning Council and the Boston Green Ribbon Commission.

Why a concern

The NOAA Tide Gauge indicates Boston Harbor’s sea level has risen 11 inches since 1920, 3 to 4 times faster than the US average

According to a World Bank study Boston is ranked 8th among cities globally for risks from damaging floods

A US Environmental Protection Agency report shows storm intensity has increased 67% over the past 60 years

New England Weather records show severe storm frequency has increased from 1 in 50 years to 1 in 5 years

The Boston Harbor Association’s report Preparing for the Rising Tide shows approximately 30% of the City is low-lying, built on filled tidelands and portions of Boston University are located on these filled areas

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and National Climate Assessment (NCA) projections indicate a future that will get considerably worse unless we can quickly and substantially cut our greenhouse gas emissions

Hazards

Preparing the University for climate change differs from preparing for weather-related emergencies: climate change is persistent, and weather is irregular. Emergency planning is only one of many important elements of our strategy for a climate ready campus. The University’s success in managing emergencies and climate-related impacts also relies on the community’s infrastructure and external partners.

Climate Ready BU will provide guidance about three hazards BU faces—flooding, heat and storms— and will suggest strategies to help mitigate the potential damage they represent. The BU study is intended as a tool to guide decision-making over time, within a climate preparedness framework. Many of these recommendations share strategies with best sustainable site and building design practices.

Flooding

The Challenge: Sea level rise compounded by storm surge, increasing rainfall intensity and low surface permeability have dramatically increased the flooding risk on campus. In almost every climate projection explored in the City of Boston’s vulnerability assessment, BU will experience flooding with increasing frequency. The City’s position is to distribute the responsibility to individuals and institutions.Recommendations:

- Implement an “if you touch it, raise it or protect it” policy for vulnerable systems

- Increase permeable landscapes and pavement to reduce stormwater runoff

- Incorporate resilient design standards for vulnerable buildings

Heat

The Challenge: Increased temperatures due to warming across the US are exacerbated by the Urban Heat Island Effect in Boston. As a result, a 124% increase is expected in the need for cooling demand. Heat extremes and droughts will stress existing energy infrastructure and resources. By the end of the century temperatures in September could average 92F. September averages will be higher than todays summer maximum of approximately 85F.Recommendations:

- Implement a heat island reduction plan with white roofs and pavement

- Implement a tree canopy extension plan

- Implement natural ventilation strategies and increase building air conditioning capacity

Storms

The Challenge: The frequency and intensity of extreme storms has already begun to increase. During these storms, high winds can peel back roof membranes and force rain through the building envelope causing significant interior and exterior building damage. If the University cannot rebound quickly, severe storms and flooding can profoundly impact the continuity of the University’s education and research mission.Recommendations:

- Account for external vulnerabilities in emergency preparedness planning

- Implement a plan for tight building envelope in new construction and renovations

- Develop an energy plan combining efficiency, on-site power and geothermal energy

Area of First Concern

Not complacent with being comfortably located behind the Charles River Dam, the GIS graduate student team explored other potential pathways for seawater to reach campus before the dam is overtopped. The elevation of the Charles River Dam is MHHW +6.8 feet. MHHW (Mean Higher High Water) is essentially the higher of the two daily high tides. The GIS team determined that the BU campus is likely vulnerable to coastal flood levels 2.6 feet lower than the dam – at MHHW +4.2 feet. This is the elevation of a low point on the Fort Point Channel’s sea wall near the Massachusetts Turnpike. If the GIS data is correct, at sea levels above MHHW +4.2 feet, seawater can spill into the Massachusetts Turnpike viaduct (a cut through the city) from Fort Point Channel westward to the Muddy and Charles Rivers. The Massachusetts Department of Transportation has now included this area of concern in their system vulnerability study, and will have a land survey of the area completed this spring to confirm the accuracy of the BU GIS study.

Boston’s original landform, known as the Shawmut Peninsula, was connected to the mainland by a narrow, low-lying causeway. This provides another area of concern, as coastal floodwaters can cross the original causeway elevation and reach the Charles River from Fort Point Channel once sea levels reach MHHW + 5.8 feet.

Working in Parallel

Other low-lying potential pathways have been identified in vulnerability assessments being conducted for the City of Boston and Green Ribbon Commission, and by teams from the University of New Hampshire and the University of Massachusetts Boston.

In addition to the City of Boston, numerous other organizations are engaged in assessing local vulnerabilities, including the Boston Water & Sewer Commission, the Boston Green Ribbon Commission, the Massachusetts Department of Transportation, the City of Cambridge as well as other coastal communities.

The fundamental challenge planners and designers face is the prospect of designing for an uncertain future. This is not what we were trained for. Designers respond quite effectively to well-defined problems, such as a 100-year storm with flooding of a clearly identified line on a FEMA map. Even the recently updated FEMA maps, however, are based only on historic data. They represent the best case, and do not in any way account for projections from the IPCC or NCA.

The City of Boston and organizations like the Urban Land Institute, The Boston Harbor Association and the Boston Society of Architects are deeply engaged in developing approaches to make Boston ready for climate change. Solutions range from keeping the water out with a storm surge barrier linking inner harbor islands, to letting the water in with a network of canals interlaced with the existing street grid.

The public discourse to prepare the city for climate change is robust and constant. Proposed solutions such as the ones illustrated above only begin to bracket the problem. The challenge is profound and can be overwhelming if we do not think creatively. Many questions remain; in fact, many questions have not even begun to be defined. The Commonwealth of Massachusetts and the Mayor of Boston have taken on the challenge and are working to develop solutions. Coordination will be critical. Since water follows landform boundaries, not jurisdictional ones, the Mayor of Boston is hosting a mayors’ summit with the surrounding communities this spring to exchange ideas for shared solutions.

What we’re doing at Boston University

The first order of design for resilience is reducing consumption: the less you have to provide during an emergency, the longer your organization can function. While the University has grown 14% since FY2006, we have reduced our water consumption by 13% and energy consumption by 4%. We are aggressively pursuing a 10% reduction in energy use by the end of FY2017.

Where we can, we are building for resilience. The nine-story Center for Integrated Life Sciences and Engineering begins construction this summer. It is being built without a basement, and the building’s critical electrical and mechanical equipment will be located on the second and third floors. Though more difficult in existing buildings, the University also considers resilient design strategies for major renovations.

We continue to plant more trees on campus, and have begun to incorporate green infrastructure in site design for new projects to reduce stormwater runoff. We are also installing white roofs for heat island reduction, and a green roof for the multiple benefits of heat island and stormwater runoff reduction as well as improved energy efficiency.

As the risks from the impacts of climate change increase in the coming years, now is the time to plan, prepare, and invest to address these risks and work to reduce costly reactive emergency management, including remedial repairs and replacement. With equal urgency, we must mitigate climate change and effectively reduce concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. If we fail to do so, the design solutions outlined here will seem rather quaint. – Dennis Carlberg

—

Though it may seem rather daunting to look out across serious storm and flooding risks to avoid becoming the next New Orleans’ ninth ward, it can also be encouraging to see regional leaders from across university, city, profit and non-profit sectors engaging in this level of innovation dialogue to co-design solutions.

Want to learn more from the BU/Boston team? Join them, @sustainableBU, alongside @SneDesai and other clean energy leaders during our #cleanenergyu conversation with Earth Week to ask them how…