Code Green Solutions

“If you don’t measure it, you can’t manage it.” How often is this ignored in the operations and management of buildings? An energy services company representative recently mentioned during a presentation, “Every mechanical room I enter has equipment that is not working properly.” The group he said this to nodded in agreement.

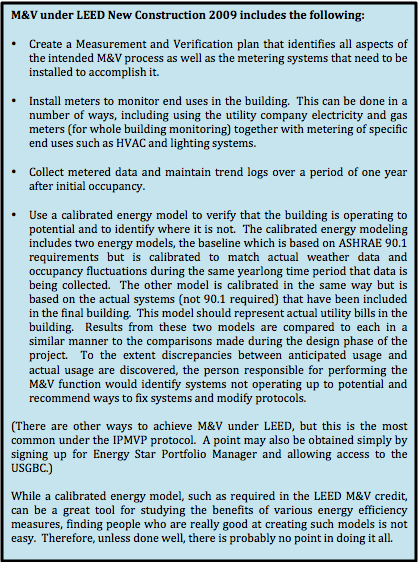

Measurement and Verification (M&V) can be an excellent vehicle for facility managers and building operators to maintain the long-term health and efficiency of their buildings. There are many interpretations of what M&V is – some might say it is a LEED credit; others might view it as a version of on-going commissioning. Under LEED New Construction 2009 (v3), M&V is intended to verify that the systems designed into a facility through the LEED process actually work as anticipated during the first full year of operation, and that the facility experiences the anticipated energy savings (or more accurately, avoided energy use). Other interpretations of M&V may include the measurement and monitoring of building and system performance over the life of the facility, similar to on-going commissioning requirements in LEED EB-OM.

Helping building operators and facility managers understand how systems in a building are operating after construction completion and during building occupancy could make a huge difference in terms of building operations and energy savings. However, the LEED New Construction 2009 credit for M&V is, in a sense, a snapshot in time – it is only required during the first year of occupancy. There is no requirement to continue with M&V beyond that year. For those who only want the LEED points, the LEED M&V credit, which is based on the International Performance Measurement and Verification Protocol (IPMVP), may fall short of expectations.

Despite shortcomings, including potentially high cost, a significant benefit of the LEED M&V credit is that it requires metering and monitoring that, if continued over the life of the building, could provide the data to enable verification that the building continues to work to its potential for a long time. Unfortunately, many people don’t recognize this opportunity and more to the point, most people don’t even use the standard tools that are included in most buildings, such as the building automation system and utility bills, to perform continuous monitoring and tweaking of systems. Without a long-term commitment, the M&V credit can be a pretty pricey credit to go after due to the metering and energy modeling that is required.

In my experience on many LEED New Construction projects, the M&V credit is one of the least achieved credits. We generally believe that it’s a good idea, but when the design team and owner look at the cost, it is often decided that there are better ways to spend money. However, even if a building decides not to check off the M&V credit on their LEED checklist, it doesn’t mean that doing some sort of M&V isn’t a very good idea. After all, if you don’t measure how well your building is operating, how will you know that it’s operating at peak potential? This is important for all buildings, and especially important for those with complicated or unique energy efficiency measures designed to maximize building performance.

The USGBC has completely revamped the M&V credit for LEED New Construction v4, possibly because of some of the drawbacks discussed above. Now, instead of requiring an M&V plan and adherence to the IPMVP protocol, projects can achieve a point for installing advanced metering, including whole building metering and metering of every end use that is 10% or more of the total load. Meters are required to provide both consumption and demand data and to provide it in a remotely accessible form. While building owners may still view this as too expensive, this new credit provides the tools for continuous monitoring of systems. That said, there are potentially less expensive systems, systems already included in your building, which can provide you with the information necessary to understand your building’s operations. Additionally, as Mark Stetz of Stetz Consulting pointed out to me, “Hardware is not a substitute for paying attention. You need the hardware, but you also need to be disciplined to use it.”

I discussed some of the advantages and pitfalls of M&V for LEED projects with a number of professionals. Paul Tseng of Advanced Building Performance, Inc said that he has not been satisfied with the results of M&V. In his experience there is often no follow through on the part of the owner and no personal investment on the part of the operator, both of whom can scuttle the advantages of any green building initiative. In fact some operators are afraid of M&V, perhaps afraid of “airing dirty laundry.” Additionally, if the project is a speculative office building, most of the energy costs are a pass-through, so operators may wonder, why bother? That said, Tseng believes that M&V is very important and provided some thoughts on how it could be carried out cost-effectively:

I also discussed M&V with Gerald Kettler of Facility Performance Associates who agreed that watching trend logs on a daily basis is very useful to identify unexpected anomalies. His suggestion – don’t get fancy. In some places, the utility provides “smart” meters that provide 15 minute daily intervals. You can usually obtain both consumption and demand data either in real time or a day late. He suggested an even simpler way to observe usage — look at your utility bills and enter the values in a spreadsheet prior to passing it on to the accountant for payment. If the information is graphed over a period of time, you can see if the building is performing as expected.

Kettler suggested that sub-metering is useful as well, but one has to be smart about it, especially on large buildings where such metering can become quite complex. In other words, metering needs to be considered early in the building design in order to make sure similar end uses, such as lighting and lighting controls, are properly grouped together to make measurement easy. Any specialty use, such as a data center, should have its own meter. While a building automation system doesn’t measure power, it can be used for M&V if temperatures, operating times and other factors are monitored and trend logs are maintained. Also, there are simple metering devices that can be clamped onto panels or that can measure how lighting operates – does it turn on and off as it is supposed to on a daily basis?

An excellent example of a project that used continuous measurement and verification to improve operational efficiency in its first two years is the LEED Platinum Jewish Reconstructionist Congregation of Evanston, Illinois (30,000 sf). LEED M&V was not attempted for this project – it would have been an expensive point. However, Alan Saposnik, the then President of the synagogue and the overall project manager for the design and construction of the facility took it upon himself to observe building operations via the BAS for two years after the project was completed. Due to his vigilance (he could view trends on his home computer) and assertiveness in getting the contractor to fix systems so that they worked properly and as designed, Saposnik caused the building’s energy consumption to decrease each of those two years. Based on a calibrated energy model, energy cost was reduced relative to the ASHRAE 90.1 baseline by over 60%! The initial energy model predicted a 35% savings. Saposnik continues looking at those trends to this day.

It is interesting how utility data and trending can be used to help identify a potential problem. A property manager asked me if we could help her reduce her utility bills by 25 cents/sf as they were that much higher than the BOMA Experience Exchange suggested they should be – a great example of a property manager looking at utility bills. However, no one was looking at actual building operations and determining that something might be wrong with some components in the system. It was clear, however, that  something needed to be done as the building was having a hard time maintaining temperature during warm summer days of 86F or so. The chief engineer, who had been with the building since opening, recommended adding a new chiller to remedy this problem. This expensive approach, which by the way, would not have worked, was not based on having observed trends in building operations. However, the assistant chief let on that there were some problems with the electric-pneumatic switches in a handful of the VAV boxes, which meant that air that was supposed to go into the space went into the plenum. After retro-commissioning the VAV boxes, changing many more of the switches than he had imagined would be necessary and calibrating/changing out thermostats, the building began to maintain temperature without the addition of a new chiller. Additionally, the 25 cents/sf savings was achieved. While the property manager took the utility bills seriously, there had been no accounting relative to the energy consumption of end use equipment in the building.

something needed to be done as the building was having a hard time maintaining temperature during warm summer days of 86F or so. The chief engineer, who had been with the building since opening, recommended adding a new chiller to remedy this problem. This expensive approach, which by the way, would not have worked, was not based on having observed trends in building operations. However, the assistant chief let on that there were some problems with the electric-pneumatic switches in a handful of the VAV boxes, which meant that air that was supposed to go into the space went into the plenum. After retro-commissioning the VAV boxes, changing many more of the switches than he had imagined would be necessary and calibrating/changing out thermostats, the building began to maintain temperature without the addition of a new chiller. Additionally, the 25 cents/sf savings was achieved. While the property manager took the utility bills seriously, there had been no accounting relative to the energy consumption of end use equipment in the building.

Stetz pointed out that a useful tool, available for free, is the Energy Star Portfolio Manager benchmarking tool. This tool is required for both LEED New Construction and Existing Buildings: Operations and Maintenance (EB-OM) and allows a building to be benchmarked against its peers. Benchmarking, whether with Portfolio Manager or BOMA Experience Exchange, will help building operators know how their building compares to others and, if utility data is input monthly, can be used to see abnormal changes in energy consumption.

Without some sort of measurement and verification, it is not possible to know how your building is working. It is important to realize that there is more than one way to get the benefits of M&V and it does not necessarily need to be expensive. Using utility data, utility bills and your building automation system may be sufficient. If you want to get fancier and use a calibrated energy model (see sidebar) and metered data, go for it, but realize that you can learn a lot without spending a lot of money as long as you vigilantly look at your data on a regular basis. Bottom line – the M&V function should never stop. You can call it on-going commissioning – it will help you avoid spending money you don’t need to spend, improve building operations and create a comfortable environment.

Story originally appeared on Facilitiesnet.com: www.facilitiesnet.com/14148bom