Code Green Solutions

Although sustainable certification systems are often used for building evaluation, they can also be beneficial in the planning and design of urban developments. Many international organizations have devised rating systems to evaluate the sustainability of new developments, but some of the most notable include BREEAM Communities, LEED for Neighborhood Development (LEED-ND), and DGNB Neubaustadtquartiere (DGNB-NSQ). This is the second article in a two-part series that investigates the major differences between these three systems. When you compare the specific goals of the criteria that each system has to offer, there are several credits within each that are unmatched in the other two. In this article, we explore these unique credits, which represent leadership and growth opportunities in the field of sustainable community design.

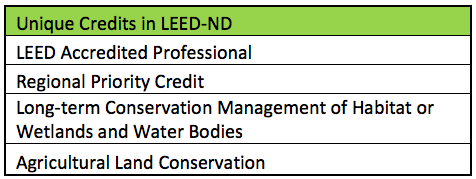

From a credit-specific perspective, LEED stands out from the other two systems when it comes to three important aspects of sustainable development: team leadership and integration, regional prioritization of needs, and environmental and ecological conservation. The LEED Accredited Professional (LEED AP) credit encourages projects to take advantage of the extensive knowledge of sustainable best practices a LEED AP would have, and then utilize that knowledge in the design process. The next unique LEED credit, entitled Regional Priority, provides additional incentive for projects in particular geographic regions to achieve the credits most necessary for that region’s environmental demands. This type of customization allows LEED to address the climate and environmental differences between projects seeking certification in different geographic locations. On the environmental side, LEED goes further than any of the three systems by specifying methods to conserve and even promote the growth of natural habitats and wetlands over time, long after the project is completed. Additionally, the Agricultural Land Conservation credit further distinguishes LEED as a system dedicated to the conservation of natural resources beyond energy and water.

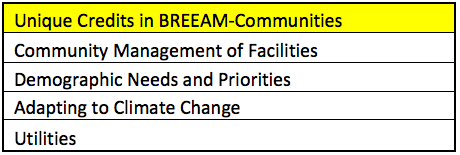

As mentioned in the previous article, one of BREEAM’s most defining features is its emphasis on the involvement of the community in the development process. To that end, the system includes two very specific credits that require additional effort to ensure the population’s needs are met. The first is Community Management of Facilities, in which developers are required to provide support for local facility managers in the transfer of the newly built properties to their control. The second, entitled Demographic Needs and Priorities, requires a detailed survey of economic impact, policies, and consultation with the community in order to determine what services, housing, and amenities are most appropriate for the development. Both of these credits underscore the importance of a community’s most valuable asset: its people. Another singular feature of BREEAM Communities can be found in its explicit approach to climate change impacts. To this end, the system includes a credit devoted entirely to mitigating the impacts associated with changes in global weather patterns, labeled Adapting to Climate Change. Furthermore, the Utilities credit separates BREEAM because of its specificity related to infrastructure access. Under this credit, easy access and room for expansion are required of the community’s gas, electricity, water/sewage, and other utility lines.

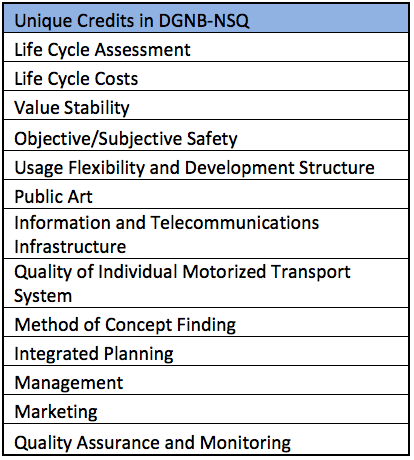

The DGNB-NSQ rating system has by far the highest number of unique credits, with 13 in total. Part of the reason for this is the scheme’s fragmentation of credits that are otherwise grouped together as well as its explicit requirement of measures that are implied in the other rating systems. Two examples are the Quality of Individual Motorized Transport System credit, which gives guidance for designing motorcycle transportation, and the Information and Telecommunications Infrastructure credit, which would likely be addressed under the general infrastructure requirements of a development. The Usage Flexibility and Development Structure credit similarly gives specificity to a particular aspect of infrastructure development that is neglected by other systems: its ability to adapt to new community needs.

This certification system is also distinguished by its devotion to economic principles, with three unique credits devoted specifically to that end: Marketing, Value Stability, and Life Cycle Costs. Although Marketing is technically part of the Process Quality group of credits, it is nonetheless aimed at securing the financial prosperity of the development through advertisement. Moreover, Value Stability requires detailed analysis of the unemployed, buying power indicators, and land values. DGNB applies a comparable level of specificity to its design- and construction-related credits: Management, Quality Assurance and Monitoring, and Integrated Planning. The Management criterion is set aside entirely for the purpose of evaluating the quality of the project manager’s work on the project. The Quality Assurance and Monitoring credit is essentially the equivalent of a commissioning credit in another system, and requires documentation of the appropriate tests for facilities in the district. Integrated Planning is intended to integrate major stakeholders from all segments of the construction process into the development design, not unlike the Integrated Process Delivery technique employed in the U.S. The remaining two credits seek to improve the quality of the urban district being certified, but in other contexts would likely not be readily equated with environmental sustainability: Objective/Subjective Safety and Public Art.

While the effect on sustainability of each of these program goals may be up for debate, the intention of each of the three rating systems is clear: to facilitate the design and planning process of high-functioning communities around the globe.

For a discussion of the differences in focus categories between the rating systems, see Sustainable Community Design part I: Thematic Emphasis.